The sound reached her over the babble of voices and the background drone of traffic.

Funny, isn't it? The way certain sounds can bring back poignant memories ... in just a split second, something buried deep in one's mind, springs forth vividly, triggered by a sound ... The way, even years later, we can recognize somebody's voice? Even though we haven't seen them, and barely even thought of them for several years, their voice is unique.

She'd have known his anywhere.

Hers was not a love story with a dramatic start, nor a dramatic ending. There was not a eureka moment, no crash of thunder, nothing of any note to it really. Not really. Hers was an ordinary love story, without guile or guilt. Oh, there was passion - of course! - and there were tears - that was inevitable. But it wasn't a story you'd think you could tell, nor one you'd think would stay in anybody's mind, let alone hers.

She barely reacted when she heard his voice. But she knew it instantly. She didn't raise her head. She didn't glance round. And if she had done so, it would have been out of simple curiosity. What does he look like now, that man ? Would he know me ? Would he care ? And anyway, what do I care ? What do I care ?

She bent her head down to her son's shoe and tried to be interested. He was past the age when she could choose for him. In fact, he wasn't even interested in her opinion, in typical teenage fashion, as though she was some ancient creature from a different world who knew nothing.

Funny how they all go through that phase, isn't it?

"Ready, Ben ?" she asked.

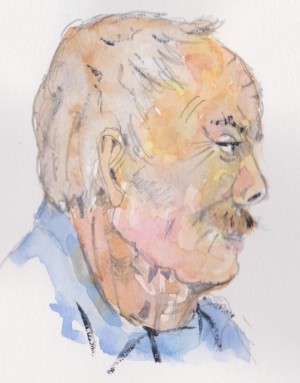

She went over to the till and paid and, as she turned, she permitted herself a glance at the man. She was conscious that her heart missed a beat, just momentarily. There was the slightest hint of a tightening in her throat. Well, she hadn't expected him to have not changed at all, she comforted herself. Of course it was a bit of a shock. Rick - that same thick brown hair that tumbled lazily over his forehead. She could even see those piercingly blue eyes. Not tall, but undeniably good-looking, he had not changed one iota. As though he somehow made time stand still. She could ... just for a split second ... recall his body odour, feel the warmth of him. She recognized that posture he always adopted when standing still, one hand in his pocket, more weight on one leg than the other. He was looking down at a small boy of about three or four.

The child, struggling with a sock, looked up and Rick then crouched down to help. He was saying something about socks and toes, and she heard the child call him daddy.

Ben had sat down again and was replacing his old shoes with the new ones, grubby socked feet up on the bench.

"Thanks mum, these are great!" he exclaimed.

"That's OK, Ben," she replied, perhaps slightly loudly, "they look good. Sure you want to put them on now?"

But Rick didn't react. No, he wouldn't, would he ? Although she would always remember him, he probably didn't remember her at all. She calculated. Do you know, that is twelve years ago now ?!

That was him through and through, wasn't it ? It wasn't that he was selfish, it was more that he just didn't register things. He made decisions and acted on those decisions. He had forgotten her very quickly, and that was that.

She had been one of his decisions. So had Ben.

Ben was two at the time. The first time she saw Rick one frozen January day by the pier in Brighton. The wind whipped in over the Channel and it was not pleasant to be out. The sun was hidden behind thick rainless cloud, and had been for several days, and huge seagulls dipped and cried on the air streams. For a long time afterwards she hated the sound of seagulls. Some men were working on a steel structure of some kind just off the beach, and she stopped, thinking it might entertain Ben. But the child was not interested and sat woodenly in his buggy, thoroughly huddled and almost immobile in anorak with yellow lambs, and several wooly things. I'll get him home, it's too cold, she thought, and she swung the buggy round.

She didn't see the man, or him her. Head down against the cold, the man was dashing by. She was never certain whether he tripped over the edge of the buggy or whether she ran the buggy in to his legs ... but the buggy tipped over and the man went with it. Later he told friends he was spread-eagled like a human sacrifice - splat! - on the pavement, but that wasn't true. He sort-of stumbled, could have fallen, righted himself and instantly bent to right the buggy.

"You idiot!" she screeched, checking Ben for injury, worriedly looking in to the bewildered little face, "why don't you look where you are going?!!"

"I'm sorry," replied the man, "but I don't think he is hurt. I am so sorry about that."

She saw that he held Ben's hat in his hand and she snatched it away from him and pulled it back over Ben's ears. She calmed herself.

"Sorry," she said, "I am sorry too. I didn't mean to yell. I was frightened, that's all."

That was all. There was no thunderbolt. He apologized again and they went their separate ways.

It may have been that he had followed her. He always denied it emphatically. Said it was coincidence. But such a coincidence in a city like Brighton didn't seem plausible. But it may have been coincidence. Who could say ?

He was standing outside her block of flats, just behind The Lanes, leaning against the door frame and reading The Times. It was about three days later.

Their love affair was ... well, just like a love affair. Sometimes intense and passionate, but also about getting to work on time and getting some food in. There was Ben to take to the childminder and the dustbins to put out. Life, with love or without it, goes on.

And she was so in love. Total and complete love. I love you, I love you, I love you she told him. And he laughed and kissed the end of her nose, her nipples, her feet. He never told her he loved her but he didn't have to - it was written all over his face.

He was remarkably good with Ben. Said he liked kiddies. He had a car seat installed in the back of his car and, as his flat was considerably larger, bought a rocking horse and rigged up a small bed that could be folded away. Once she asked him if he already had a child, for he seemed such a natural - would even absently jiggle the buggy if Ben was fractious, or pick up a dropped toy.

Winter limped greyly in to spring. The huge waves that had crashed icily on the Brighton pebbles calmed a little and scudding clouds heralded the approach of warmer days. There was a faint smell of grass in the air and the purple shadows of winter faded in to blue. Together they attached window boxes to the balcony windows of both their flats and planted primroses and violets. They hung up bird feeders and Rick tried - oh, totally unsuccesfully! - to take photos of the wrens and tits as they hovered to peck out the seeds. Starlings built their nests under the eaves of Rick's building and made such a lot of noise once the eggs were hatched. Such a lot of noise. That was another sound that stayed with her for a long time.

Occasionally his work took him away for a few days. He was in banking - something complicated no doubt. She worked in a clothes' shop. Sometimes she feared she seemed a little daft by comparison, but if it was so he didn't show it.

"Shall we go to Corfu?" he asked suddenly one evening.

"Corfu?" she asked, "how d'you mean shall we go?"

"A holiday?"

"Oh!" she laughed, "I can't possibly afford it!"

"Well, I can," he said, and she realized then that he had already booked it.

Lovely surprise jarred against irritation at not even being consulted. Surprise won.

Ben loved the beach. They spent evenings on their hotel balcony, often having food delivered to the room so that Ben could sleep safely. They strolled through the little streets. They held hands, kissed, made love. He bought her way too many presents. He bought Ben way too many presents. He was fun, laughing, indulgent.

Happiness is so huge when you are happy. It is wide. It covers the sky. It encompasses you.

She told her parents about him. She told everybody about him.

"Is he Mr Right?" asked her mother, delightfully old-fashioned.

"Yes, he is. He is The One. We get along brilliantly and he adores Ben. He hasn't said anything ... I think he just assumes that we are together now and that one day we'll move in together, get a bigger place ... We just haven't started talking about it."

"It must be getting on for a year now?" her mother then said. "Early days still!"

Summer faded off in to the faraway places and leaves trembled and started to fall. The warmth in the sun decreased and a thin wind scuttled through The Lanes, bringing with it chilly mornings and darker evenings. They spent more and more time together in his flat where there was an open fire. Cosy evenings with wine and nuts and a good movie while the toddler slept. The Christmas lights came on in the streets, and dipped and twinkled against the dark sky. They got a tree and decorated it together. They all went to her parents' house in Hove for Christmas lunch. On Boxing Day they lolled by the fire in his flat.

"I'm being transferred to Tokyo," he said suddenly one evening.

It was just over a year since the buggy incident. Rain beat against the window panes of her flat - they were in her flat. They had popped into fetch spare clothes for Ben. She didn't understand. Was this another holiday coming up ?

"Tokyo?" she asked. Sounded interesting!

"Yep, it's a great opportunity!" he grinned.

"Yes, sounds it! Tell me more!" Even then she didn't twig. Well, why would she ?

"I've been waiting some time for a transfer to somewhere exciting. They proposed Brussels to me a few months ago but I turned it down. Pay was no better and the transfer not for another year anyway."

You know how you can think whole paragraphs in a split second ? The way you can recall twenty conversations and forty scenarios in the blink of an eye ? Various scenes and possibilites fled through her mind as she tried to assess what he was saying. She needed to pack things, sell things - when were they off? She couldn't handle this so suddenly ... Then she looked at him.

"You mean you are going to work in Tokyo?" she asked quietly.

"Yep!" he was pleased.

"When?"

"Within the month!"

It didn't seem to occur to him that perhaps she wasn't pleased. But it occurred to her, with a dry creeping sensation, that she wasn't included in his plans.

"Rick," she said, "tell me this is a joke."

"A joke? No. Why a joke?" A look of mild irritation crossed his face fleetingly.

"Where do I fit in to this?" she asked quietly, "where does Ben fit in?"

They stared at each other in silence.

"I'm sorry ..." he said at length, "I am ... truly ..."

"I thought we meant something to you, me and Ben?"

"You do! Of course you do! I shall never forget you ..."

The sound of the silence in the room. Full, heavy silence. The sound of the rain against the window. Somewhere a car hooted out in the street and a man called out after a dog. And the silence.

"Of course you've meant something to me ... you've meant a lot ... and it has been great. Really."

More silence.

"It's just that I am going to Tokyo. That is all."

And that was all.

She had cried for months.

She looked over to where he was with his little boy. They seemed to have chosen a pair of trainers and were heading for the till. She didn't turn around but got out her mobile phone. From the periphery of her vision she could see him stop suddenly as he recognized her. He stepped forwards towards her, his arm rising to shake hands. She allowed her eyes to glide over him as she raised the phone to her ear and simultaneously nodded to Ben to head for the door. Rick's eyes were fixed to her. She looked straight through him as she said something in to the phone, and then let her eyes glide off to something beyond him. She saw him hesitate as he realized she hadn't recognized him. He turned away.

Out on the street the sounds of the day filled her. Cars, buses, people, seagulls. She walked briskly as Ben got out his MP3, up the street to Costa's where Phil and Daisy were waiting. Oddly enough, Daisy was wearing that same old anorak with the yellow lambs.

The End.